Polls & Surveys

The New Coalition?

While falling well short on some key issues, it’s been heartening at least to see the Federal Coalition leading the discourse and taking some risks on genuine reform.

Left in ruins after being swept from office in 2022, many commentators questioned the viability of the Liberal party. But within two years they have surged back into relevance, and with a flavour less antithetical to libertarians.

It began early in 2023 when the National Party declared its stance on the Voice referendum, and Dutton duly followed, despite some resistance within the Liberals. This crucial first step allowed Australians to see that Dutton’s Liberals were delineated from Labor, and despite healthy early polling for the ‘yes’ case, Dutton’s gamble paid off handsomely and the Albanese honeymoon ended abruptly.

The Liberal state divisions are much slower on the uptake, as evidenced by their staunch refusal to adopt Dutton’s nuclear proposal.

Then, whispers on vaping prohibition, super for housing, an overhaul of immigration, and of course the big one: nuclear power. Nationals deputy leader Perin Davey was even floating the idea of income splitting between household partners! Recognising his lack of personability and charisma, Dutton has opted to take a series of policy reforms to the next election with an eye to vastly expanding the Coalition’s electoral map as its traditional base shrinks.

Lo and behold, they have already taken the lead in several recent national polls and, incredibly, Dutton overtook Albanese as preferred PM in the latest Resolve poll – something I thought I would never see. It may be that in time Dutton will again lose control of the narrative; Australians are typically sceptical of reform agendas from opposition (see Bill Shorten, 2019), but there’s some encouragement for libertarians here.

It appears the unfolding political realignment is presenting the Liberals with an opportunity to reinvent themselves as the party of working Australians. The ‘teal wave’ of 2022, that also saw blue ribbon seats such as Higgins and Ryan fall to Labor and the Greens, was a blessing in disguise. Many of the nagging progressive moderates of the party were flushed out of metropolitan strongholds, leaving Dutton with no choice but to devise a new path to victory. Thus, faced with poor prospects with young voters and the opportunity to re-home the politically jaded working class, Dutton is unveiling his new coalition.

As libertarians, we still have important work to do. Firstly, the Coalition maintains terrible policy in areas such as online safety, while their shadow cabinet currently boasts the leftovers of a government that completely failed to effectively manage the budget for a decade.

The National Party declared its stance on the Voice referendum

Secondly, the Liberal state divisions are much slower on the uptake, as evidenced by their staunch refusal to adopt Dutton’s nuclear proposal. Metropolitan centres still dominate their electoral prospects and the old risk averse attitude still prevails: in Queensland for example, LNP leader David Crisafulli is paralysed, terrified of losing an unlosable state election, while in Victoria John Pesutto and his inner city moderates still control the party.

Undoubtably, libertarians still have a major opportunity to shape public policy. While it’s encouraging to see the Coalition adopt a reform agenda with some sensible policy that promotes free choice and prosperity, they are still a long way from their classical liberal roots. At the state level, libertarians have a unique opportunity to help set the agenda and give voice to the aspirational working class. Imagine, for a moment, if the Liberal Party had spoken up on behalf of those campaigning against the excesses of Covid mania and mandates. Imagine also if they had meekly embraced bipartisanship on the Voice.

It is worth reflecting on the positive change we see in the Liberal Party. They are perhaps the most powerful vessel for libertarian policies, having proven under Dutton that they can take on the left and win. It’s indicative of our political influence in action. However, we must be merciless when they stray back towards populist authoritarianism.

FLASH POLL: Do You Support The United States-Australian Military Alliance?

There’s been a lot of talk about the US-Australian alliance, especially with AUKUS nuclear submarines attracting bi-partisan support in Australia.

Libertarians typically split on the issue of foreign affairs, geopolitics and military action.

Group one says we should maintain a self-reliant, self-defensive military and not engage in foreign entanglements. Adopting a non-interventionist policy in matters foreign, this school of thought argues alliances can put a target on our back so seeks to defend Australia if and only if directly attacked. For want of a better term, we’ll call them the “Neutrality” group.

Group two says free countries are rare, face authoritarian foes and Australia, a free nation, is vulnerable with its large coastline and sparsely-populated continent. Arguing for a robust military but knowing Australia can’t by itself defend such a land mass with few people, this school seeks foreign alliances, which include international obligations, to fully protect our freedoms. We’ll call them the “Alliances” group.

So, here’s the flash poll.

Do you support the United States-Australian military alliance?

Yes or no.

Once you’ve voted, I’ll share some thoughts on this.

Out of Proportion

Recent elections in both the UK and France highlight major flaws in their electoral systems, with lessons for Australia.

Compare the pair:

UK Labour (2024 UK election)

- National vote share: 33.8%

- Seats won (% of chamber): 63.38

Australian Labor Party (2022 Australian Federal election)

- National vote share (2pp): 52.13%

- Seats won (% of chamber): 51

How can an electoral system be considered fair when one party (Labour) can take 34% of the national vote and win a ‘landslide’ election, while another (Reform) can take almost 15% and go home with 0.8% of the seats (5 out of 650)? It’s a similar story in France, where National Rally comfortably won the popular vote but will walk away with less seats than Macron’s centrists and the NPF.

Political candidates and parties receive public electoral funding in Australia on a per-vote basis.

It highlights the importance of two key pillars of Australia’s electoral system, but also points to a couple of weaknesses.

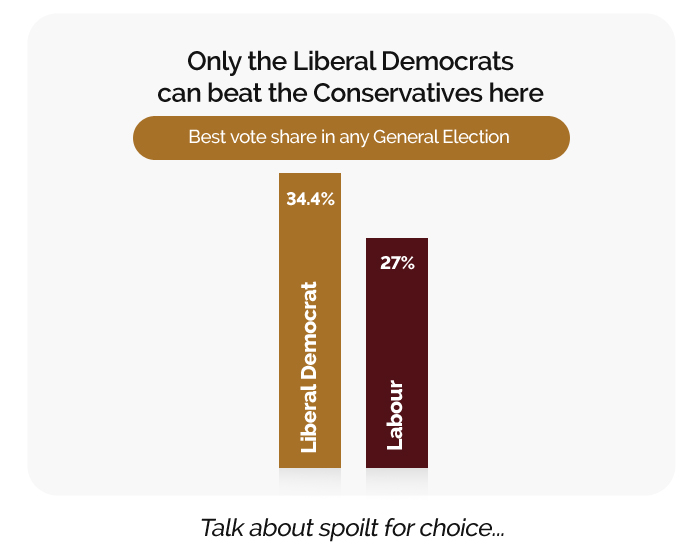

I believe the UK election highlighted the fact that first past the post voting is neither fair nor representative. In an election dominated by an almost universal will to unseat the Conservatives, Labour and the Liberal Democrats often campaigned on prior results or current polling to indicate that voters should vote ‘tactically’ to ensure the Tories lost.

On the other hand, Nigel Farage’s Reform Party did not encourage such a practice, instead seeking to simply gain votes at everyone’s expense. As a result, the right-wing vote was regularly ‘split’ and either Labour or the Lib Dems were able to take the highest vote share.

Apart from the national vote being wildly out of proportion to the composition of Parliament, it is unfortunate that parties should gain votes tactically. It is regrettable that voters, rather than choose their preferred party/candidate, feel compelled to vote for the one they feel is most likely to defeat an incumbent they dislike. There’s no way to know how many votes for each party represent a genuine first preference for them.

The secondary issue here is the lack of a vehicle for proportional representation. If the UK had a second (democratically elected) house of parliament that was elected via proportional representation, its make-up would more closely resemble the national vote share, at the same time negating the need for any tactical voting.

To bring us back to Australia, although preferential voting in the House of Representatives mostly renders tactical voting unnecessary, there are exceptions. The two-party preferred (2pp) system can influence voters under certain conditions to change their first preference in order to ensure a supposedly more viable candidate is not eliminated early – this occurred in ‘Teal’ seats at the 2022 Federal Election.

UK election highlighted the fact that first past the post voting is neither fair nor representative.

This issue is compounded by the fact that political candidates and parties receive public electoral funding in Australia on a per-vote basis. This practice should ultimately end, not only for the aforementioned factors that influence voters, but due to the ongoing advantage it gives larger political players.

The other meaningful change that I’d make to Australia’s electoral system would be to abolish any districting within our state upper houses. By creating geographic segments within the overall electorate, the vote quota needed to gain a seat increases – again locking out smaller players and denying their voters representation. In my home state of Victoria, new legislation (similar to recent reforms in WA) could remove our upper house regions, creating a state-wide proportional race for the Legislative Council.

So don’t knock preferential voting: it allows for the most genuine expression of voter intention, and proportional representation ensures even the small players take their rightful place in the chambers. The alternatives are not fit for purpose.