Little House On The Prairie: A Libertarian Story

I’m Gen X, born in 1968.

The 1970s and early 1980s were therefore my boyhood years.

We ran around the neighbourhood freely. We played. We invented. We imagined. We read. And if we were good, we were allowed to watch carefully-selected television shows broadcast according to a scheduled program published in the local newspaper.

7:30pm each Thursday was The Little House on the Prairie.

I loved it.

Its morality tales of the hardscrabble settler life met with stoicism, of the vicissitudes of life on the land, of finding ways to make a living, of building a life no matter the difficulties to be confronted, of the similarly-resourceful neighbours in support, of barely a hint of government but the post office and occasional circuit-judge were amazing adventures for a youngster who’d grow to become a libertarian.

I’m not just talking of me. Actually, a real-life character of the books and TV series went on to be a mother of American libertarianism along with Ayn Rand.

Rose Wilder Lane was the daughter of Laura Ingalls Wilder, who wrote the Little House books. Lane was heavily involved in the editing and promotion of her mother’s work, and the two women had a close relationship. Rose is portrayed in the latter season of the TV series.

Rose Wilder Lane’s political philosophy emerged later in life, though who could deny childhoods are formative. A prolific author herself, she abandoned lucrative fiction writing to explore political philosophy.

Lane’s essential belief was that individual freedom was the foundation of human flourishing, a libertarian precept. In her book The Discovery of Freedom, she wrote:

“The one essential condition of human welfare and

the happiness of the individual is freedom.”

She believed that individuals had a natural right to control their own lives and to pursue their own goals, without interference from the state.

She also focused on the importance of property rights, which she saw as a key component of individual freedom. Again, in The Discovery of Freedom, she wrote that “property rights are the most basic of all human rights,” and that they were necessary for individuals to control their own lives and make their own decisions. She saw government tampering with property rights as a violation of personal liberty.

Lane’s political philosophy piercingly advocated for free markets and competition. In Give Me Liberty, she argued that:

“The free-market system is the only one in which

people can cooperate voluntarily to achieve mutual benefits.”

She railed against price controls and regulation as harmful to economic growth and individual freedom.

Furthermore, Lane was a defender of personal liberty and freedom of speech. She believed that individuals had a right to think and speak freely, and that governments should not restrict academic freedom or freedom of the press. On these topics in Give Me Liberty, Lane wrote that:

“Freedom of speech, freedom of press, freedom of assembly,

these are not only constitutional rights,

they are natural rights, and the essence of liberty.”

Like the US Founding Fathers, Lane’s political philosophy was heavily influenced by the ideas of English philosopher and father of liberalism, John Locke. In this way, American conservatives seek to conserve liberalism and its philosophical child, libertarianism. Like Locke, Lane believed that individuals have natural or God-bestowed rights that pre-exist government, and that the role of government is to protect these rights. She also shared Locke’s emphasis on property rights and free markets.

In her essay Credo, Lane directly cites Locke’s work as an influence on her own political philosophy:

“John Locke laid down the principles of Americanism:

that government exists to protect individual rights,

that the government is the servant of the people,

and that man is entitled to his life, liberty, and property.”

Moreover, Lane saw her political philosophy as a continuation of the American founding tradition. In Give Me Liberty, she wrote: “I believe that Americanism means the recognition of the individual as the centre of all things, and that the government exists solely to protect the individual rights of the citizens.”

These are libertarian principles.

Maybe eeking-out a harsh life on the Minnesota and South Dakota prairies bred this libertarian. I’ve written before about flinty, rural, self-reliant types in the Adelaide Hills in Just Another Day Battling A Government Agency. It’s the same trait and worldview.

If you have Gen Z or Zoomer children and you’d like to prepare them for a life of resourcefulness, freedom and independence from the state, I recommend the Little House books by Laura Ingalls Wilder and the 1970s TV series. And when they are older, I recommend the writings of her daughter, Rose Wilder Lane.

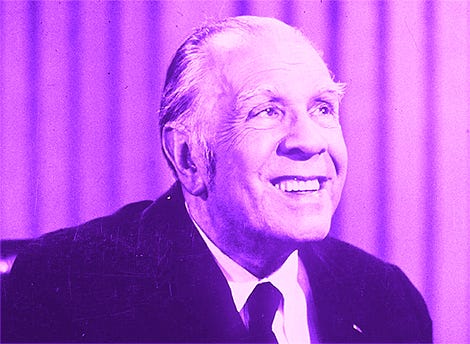

Mother of the American libertarian movement.