Geopolitics and The Non-Aggression Principle

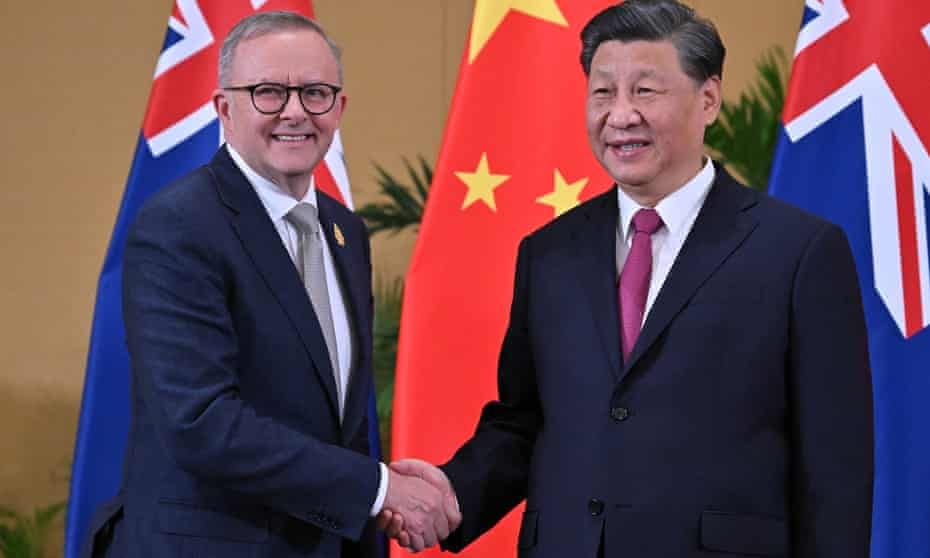

For an example of how libertarians philosophically wrestle, behold this exchange between the Arizona Libertarians and Australian Brett Lombardi:

It is eloquent in its brevity: realpolitik confronting Rothbardian idealism.

One of the foundational concepts of libertarianism is the Non-Aggression Principle. Put simply, this is the idea that violence and coercion between parties should be avoided, and that people should act cooperatively and in harmony.

It has mainly been applied to situations between individuals. But what about non-aggression between nation states, the geopolitical sphere?

Enter libertarian heavyweight, Murray Rothbard:

In National Defence and The Theory of Externalities, he wrote:

“For the libertarian, the key to foreign policy is the defence of the homeland against aggression. The State should protect the citizens, keep the peace, and defend person and property from attack.”

Straightforward enough, it seems. But what is ‘homeland’?

Let’s put the Rothbardians to the test with a series of scenarios, asking whether each is a violation of the Non-Aggression Principle:

– The Chinese Navy sails to Venice Beach, California, with amphibious craft landing and troops shooting people. I’m sure we can agree this violates the Non-Aggression Principle.

– What if US surveillance determined in advance that the Chinese were coming and warned them not to enter the 12 nautical miles of US territorial waters? The Chinese ignore and enter, then the US engage the aggressor at 11.9 nautical miles? Is this a Chinese or US violation?

– What about at the US exclusive economic zone boundary of 200 nautical miles? If US engages, is this a violation?

Libertarians must be practical and realistic in geopolitics to achieve electoral success.

Rothbard doesn’t say what the ‘homeland’ is but would probably pick one of these boundaries.

But we can test this further:

– In 1893, US agents and businessmen mounted a successful coup against the Kingdom of Hawaii, asserting that their investment and private property rights were under threat. The US “annexed” Hawaii in 1898 as a territory. Did the US violate?

– Then in 1941, Japan bombed this territory. Hawaii wasn’t even a state of the US at the time of the Pearl Harbour attack. Were the US defending their ‘homeland’ when it used anti-aircraft fire against the Japanese, or were they in continued violation of the Non-Aggression Principle because of their prior military-backed coup?

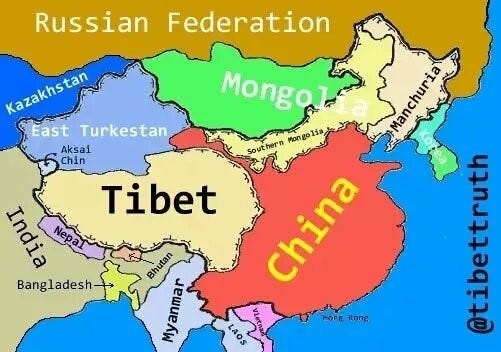

– What if the Chinese today invaded Guam or American Samoa, both mere territories as Hawaii was? Would this be a violation? Both locations are closer to China than the US. Where does US ‘homeland’ end?

Rothbard doesn’t define the extent of the US homeland, but I suspect he might regard these territories as empire-building and so in violation of the Non-Aggression Principle.

He heavily criticised Gulf War I as an example of creeping empires in The Case For Radical Idealism:

“In foreign affairs, the libertarian sees the danger and evil of the U.S. launching an aggressive war against Iraq. This is why the true lovers of liberty should condemn the Bush Administration’s war, and make it crystal clear that, in their libertarian view, it is a criminal war of imperialist aggression.”

In that vein:

– What about the joint US-Australian Military Surveillance Base at Pine Gap, Northern Territory? Among its many purposes, this base is used by the US to determine whether Guam and American Samoa are under threat of attack. In an age of intercontinental missiles taking only 30 minutes to reach their targets, can the US defend this base as a defence of its homeland?

– If the Chinese bombed Darwin’s Robertson Barricks at which 2,500 US marines are based on the invitation of Australia, does the US violate the Non-Aggression Principle by defending those US marines and Australian soldiers?

– If China ‘annexed’ Taiwan, would that be a violation of the Non-Aggression Principle? If so, is it really the view of libertarians in Arizona that libertarians should merely shrug our shoulders?

Rothbard shunned territorial pre-emption yet these are realpolitik situations. I think this is a huge Rothbardian blind-spot.

Should the British have waited for Napoleon to land on the beaches of Dover? Should the Australians have met the Japanese at Cooktown rather than Kokoda? At what point should the British RAF have engaged the raiding Luftwaffe? Over Canterbury, Calais or Cologne?

Even if we just define ‘homeland’ as current national borders, there is still much to challenge us about Rothbard. For instance, in For a New Liberty: The Libertarian Manifesto, he elaborates on the type of impermissible intervention:

“A non-interventionist policy means that America does not interfere militarily, politically or covertly in the affairs of the other nations.”

Rothbard refined this further, in War, Peace and The State:

“War, then, even a just defensive war, is only proper when the exercise of violence is rigorously limited to the individual criminals themselves. We may judge for ourselves how many wars or conflicts in history have met this criterion.”

So, Rothbardian libertarians such as those in Arizona argue that defence of the homeland against aggression is permitted but that defence cannot extend to preventative measures and defensive force may only be aimed at individual war criminals!

How a commander would know, in the heat of battle, the identity of a war criminal in advance of a war crimes tribunal is beyond me.

None of these expressions of libertarianism give me much confidence that, when applied, practical benefits will result. And yet the entire point of libertarian philosophy is to spawn policies which work to unleash human flourishing.

More realism and less idealism, I say.

In this regard, I am not a Rothbardian idealist. I prefer the view of leading realpolitik libertarians like David Boaz, Executive Vice President of the Cato Institute who wrote:

One of the foundational concepts of libertarianism is the Non-Aggression Principle.

“Libertarians should be realistic about the world. Some level of military and intelligence capability is necessary for national defence and to secure the freedoms that libertarians cherish.”

And Nick Gillespie, Editor-At-Large, Reason Magazine who offered:

“Libertarians are not pacifists. We recognise that the state has a role in national defence. The key is to ensure that this role is strictly limited to protecting the country from external threats and does not devolve into unnecessary interventions.”

Or this from Cato Institute’s, Julian Sanchez:

“Libertarians should recognise that there may be cases where limited and well-defined military intervention can be justified on humanitarian grounds, such as preventing genocide.”

Let me marshal further libertarian opinion to counter Rothbard. Here, leading US libertarian Senator Rand Paul:

“While a strict non-interventionist foreign policy may have its merits, there can be instances where limited government intervention is necessary to protect the nation’s security and interest.”

And Brian Doherty, Senior Editor at Reason Magazine, who penned:

“While avoiding unnecessary conflicts is crucial, libertarians should acknowledge the importance of maintaining a credible defense to deter potential aggressors and protect individual rights from external threats.”

Yet further still, perhaps more gently, even leading libertarian philosopher and Rothbard rival, Robert Nozick, in Anarchy, State and Utopia, wrote:

“A minimal state devoted to the task of protecting rights and enforcing contract will, if minimal enough, and if rights include rights to self-defence, do all that government can do.”

So limited government intervention, doing “all that government can do” and deterrence feature strongly.

Libertarians must be practical and realistic in geopolitics to achieve electoral success. Freedom House says there are only 38 free nations in a world of 195 countries. Freedom is rare and must be protected wherever it blooms.

Brett Lombardi gets it right.