A government’s balance sheet indicates whether it is engaging in intergenerational redistribution. If the government has negative net assets it is leaving future generations with more obligations than benefits. A government with positive net assets is leaving future generations with more benefits than obligations.

Governments have no advantages over individuals in making decisions about what to leave to future generations, so should leave those decisions to individuals. This means that governments should have zero net assets; their balance sheets should be balanced.

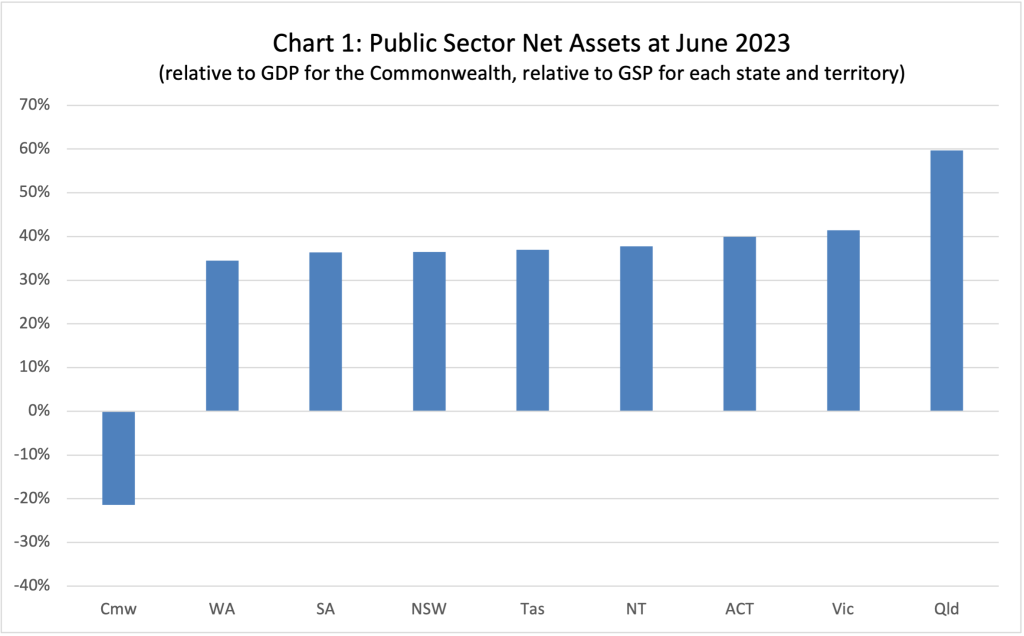

Governments in Australia do not have balanced balance sheets. The Commonwealth has a significantly negative net asset position and each of the states and territories has a significantly positive net asset position.

When it comes to setting fiscal policy, governments should ignore short-term Keynesian distractions, and focus on long-term intergenerational neutrality.

This is shown in Chart 1. It depicts public sector net asset positions relative to the size of the related economies. Commonwealth net assets are shown relative to Australia’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP), while each state or territory’s net assets are shown relative to the relevant state or territory’s Gross State Product (GSP). Each jurisdiction’s public sector includes government-owned businesses such as government-owned banks.

The Commonwealth’s negative net asset position means that it is choosing to leave future generations with obligations in excess of benefits. In essence, the Commonwealth Government has locked in benefits for future generations, like security from the military assets it has accumulated to date, but has racked up far greater obligations, like obligations to pay back Commonwealth debts and fund the superannuation of retired Commonwealth public servants.

This decision of the Commonwealth Government to beggar the future is unlikely to represent the preference of Australians.

The Commonwealth Government’s intergenerational redistribution should stop, so as to leave intergenerational decisions to individuals. In other words, the Commonwealth Government should convert its negative net asset position to a zero net asset position. This should be done through a decade of surplus budgets (or surplus ‘operating results’ to be more precise) of around 2 per cent of GDP.

This could be readily achieved, for example by reducing Commonwealth Government transfers to the state and territory governments. These transfers are particularly odd given that each state and territory government is wealthier than the Commonwealth Government.

Each state and territory government’s positive net asset position means that it is choosing to leave future generations with benefits in excess of obligations. It is teeing up more benefits for future generations, like their enjoyment of public land holdings and use of infrastructure like roads, than it is racking up future obligations, like State Government debts and funding the superannuation of retired State public servants.

While leaving future generations with benefits in excess of obligations sounds nice, this is something that individuals are perfectly capable of doing without government.

Governments have no advantages over individuals in making decisions about what to leave to future generations

And the current generation may well be of the view that the degree of generosity to future generations shown by each of the state and territory governments is excessive. If there is a difference of opinion between a government and the individuals it represents, then it is the government that is wrong.

State and territory government intergenerational redistribution should be put to a stop by each government reducing its positive net asset position to net zero. This should be done through a decade of deficit budgets (or deficit ‘operating results’ to be more precise) of around 4 per cent of GDP on average.

Such deficits could be achieved by abolishing inefficient taxes like stamp duties, or by giving away assets. (Such give-aways count as losses that detract from the operating result.)

The biggest deficits should come from the wealthiest state governments, in Queensland and Victoria.

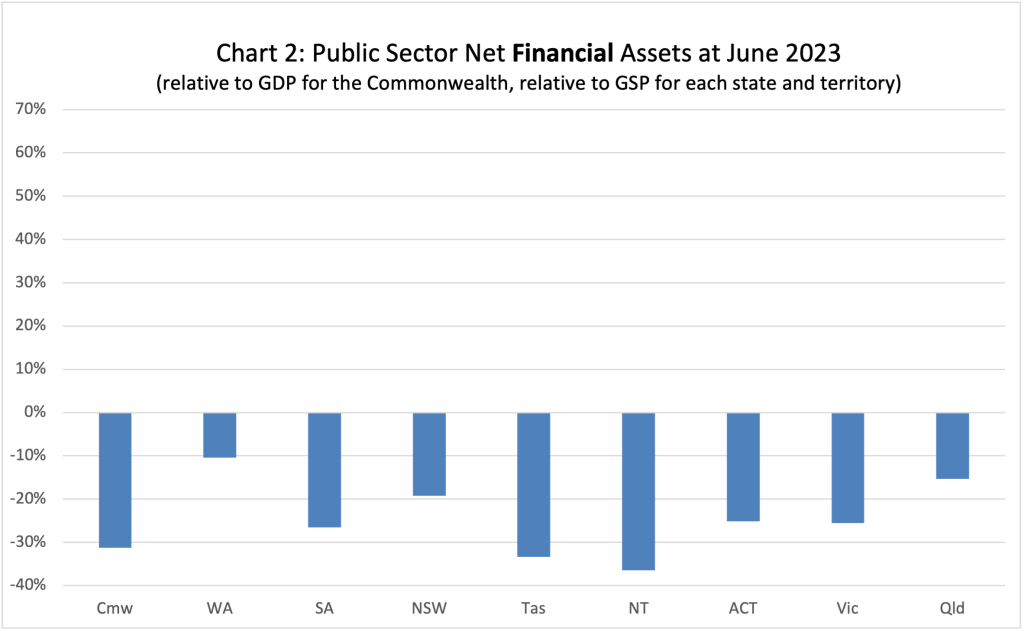

The wealth of the Victorian state government may come as a surprise. The Victorian state government has a stronger net asset position and a weaker net financial asset position than many of its counterparts (see Chart 2). It has done a lot of borrowing, which has weakened its net financial asset position, but it has done this to invest in non-financial assets. Overall this generates a positive, or at least neutral, impact on net assets.

Unfortunately for the Victorian state government, credit rating agencies tend to ignore a government’s net assets and instead focus on its net financial assets. Even more stupidly, lenders take these credit ratings into account when lending to governments. If a state or territory government wanted to defend its credit rating so as to ensure continued access to low-cost borrowing, it could still run significant deficits in line with my recommendation. It would just need to achieve these deficits by giving away non-financial assets, like land, so as to leave its net financial asset position unchanged.

When it comes to setting fiscal policy, governments should ignore short-term Keynesian distractions, and focus on long-term intergenerational neutrality.

I agree with the idea of eliminating deficits, however, the state assets belong to we the people, and state governments need no encouragement to behave irresponsibly as they are already demonstrably overqualified.

One area that was overlooked was the third tier of government, local councils, who again on paper appear to be asset rich but again can be generalised as irresponsible spendthrifts.