Libertarianism is all about the freedom of individuals from coercion. Libertarians believe the proper role of government is defined by JS Mill’s harm principle: ‘The only purpose for which power can be rightfully exercised over any member of a civilised community, against his will, is to prevent harm to others.’

Within a country this is relatively straightforward – reductions in tax and increases in liberty are supported, increases in tax and reductions in liberty are opposed.

But things can get complicated when it involves matters outside the country. How is libertarianism affected by national borders? Can it apply to relationships between sovereign states?

To what extent should Australian libertarians seek to oppose coercion in other countries?

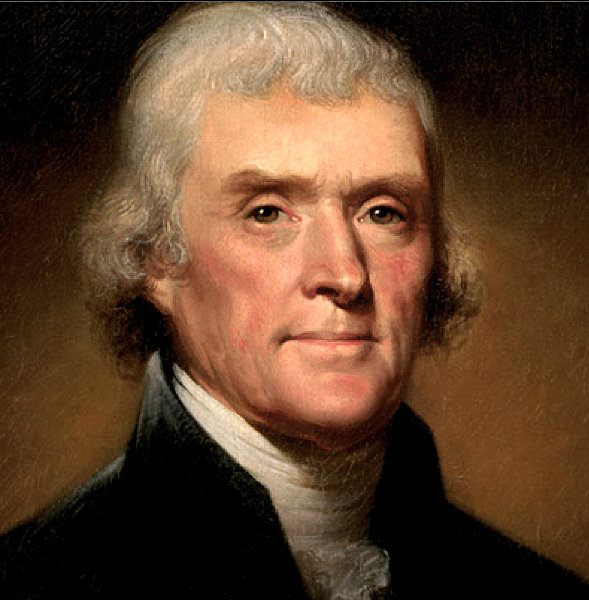

In his 1801 inaugural address, US President Thomas Jefferson declared that the US should consider its external military alliances to be temporary arrangements of convenience to be abandoned or reversed according to the national interest. Citing the Farewell Address of George Washington as his inspiration, Jefferson described the doctrine as “peace, commerce, and honest friendship with all nations—entangling alliances with none.”

Known as the Washington Doctrine of Unstable Alliances, this thinking dominated US foreign policy right up to the Second World War. And although America now has longstanding alliances with many countries, including Australia, the doctrine remains influential in some political circles.

In particular, many libertarians support it. In their view, a country should not invest blood and treasure in squabbles beyond the country’s borders unless there is a clear threat to the country and its ability to engage in trade and commerce. It should certainly not maintain military capabilities in excess of what is needed to defend the country.

This is rationalised in terms of libertarian values. History has repeatedly shown that a standing army is a threat to liberty. Moreover, maintaining a military force capable of more than simply defending the country is expensive, necessitating higher taxes than if the Washington Doctrine applied.

They point to wars such as Vietnam, Iraq and Afghanistan, where it is difficult to show any enduring benefits from military involvement by America or Australia. They also criticise current support for Ukraine’s fight against Russia’s invasion.

There is a problem with this thinking though: nationalism and national sovereignty are actually collectivist concepts. They are not libertarian and, Jefferson’s other qualities notwithstanding, neither is the Washington doctrine.

What that means is there is no libertarian justification for doing nothing about coercion merely because it is occurring in another country.

Coercion should always be our concern, wherever it occurs.

That does not necessarily mean rushing military aid to those subject to coercion in other countries. There are many reasons why that might not be possible, practical or advisable. But it is perfectly legitimate for libertarians to consider whether there is anything they can do, militarily or otherwise.

Some interventions have made a major difference. But for America’s entry into the Second World War, for example, Germany and Japan would have imposed their dreadful dictatorships on most of the world. But for America’s intervention in Korea, the people in the south would now be suffering the same miserable fate as those in the north. And but for Australia’s intervention in East Timor, the country would be suffering under Indonesia’s heavy-handed military rule, now obvious in West Papua.

There are also some current examples to consider. One of the consequences of the climate change panic, for example, is that around 40,000 children in the Democratic Republic of Congo work in appallingly inhumane, slave-like conditions in cobalt mines. The cobalt is used in lithium-ion batteries required by electric vehicles.

In China, the government has imprisoned more than a million Uyghurs since 2017 and subjected those not detained to intense surveillance, religious restrictions, forced labour, and forced sterilisations. Forced labour is used to produce solar products.

It is estimated that China has 98 percent of the world’s manufacturing capacity for photovoltaic ingots; 97 percent for photovoltaic wafers; 81 percent for solar cells; and 77 percent for solar modules. Many of the largest global producers of photovoltaic ingots and wafers, solar cells, and solar modules directly source polysilicon from entities believed to use forced labour in its production.

Even a boycott of products associated with such coercion would be more consistent with libertarian values than doing nothing based on the “no entangling alliances” idea.

JS Mill was also an advocate of utilitarianism in addition to classical liberalism. This philosophy, generally attributed to Jeremy Bentham, is often summarised as seeking the greatest good for the greatest number. For libertarians, it should mean the greatest liberty for the greatest number.

Great article. Tackles this ‘no foreign entanglements’ idea head on. Please note, US libertarian readers.