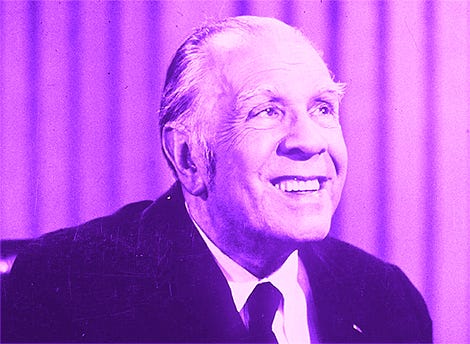

Jorge Luis Borges (1899-1986) is widely regarded as one of the most important writers of the 20th century. It’s a big call; but as someone who has been fascinated by his writings for many years, I’m not about to disagree. The Argentine is perhaps less well-known than the great novelists of the Latin American Boom, such as Nobel laureates Gabriel Garcia Marquez and Mario Vargas Llosa; and yet, Borges was a major influence in the renowned magic realism of their novels.

Borges’ body of work consist of poems, short stories, and essays. He speaks of fundamental human mysteries, life’s journey, the passage of time, the universe; mythological labyrinths, minotaurs, wars, heroes; but also, alleyways, patios, chess, and coffee.

In life and in fiction he avoided politics with questionable success. He was the target of criticism from people who thought he had a moral responsibility to use his notoriety to influence political life in every which way. He claimed to have a profound disinterest in such matters: “I know little about contemporary life. I don’t read a newspaper. I dislike politics and politicians.” [A Conversation with Jorge Luis Borges – Artful Dodge Magazine, 1980].

Borges didn’t set-out to make political statements in his work, arguing that art should be “free not revolutionary”, but he was naturally inspired by contemporary and historical events, particularly from his troubled Argentina. His political sympathies changed over time (“I was a communist, a socialist, a conservatist and now an anarchist” – he confessed later in life) but there was a consistency of thought throughout his life.

What emerges from his writings, interviews and public appearances is a political position that can be seen as ambivalent in the context of the traditional left-right dichotomy.

In an essay titled Our Poor Individualism he writes: “The most urgent problem of our time (already denounced with prophetic lucidity by the near-forgotten Spencer) is the gradual interference of the State in the acts of the individual; in the battle with this evil, whose names are communism and Nazism, Argentine individualism, though perhaps useless or harmful until now, will find its justification and its duties.” This Argentine individual “does not identify with the State”, something Borges attributes “to the circumstance that the governments in this country tend to be awful, or to the general fact that the State is an inconceivable abstraction”. It is the same sentiment expressed by Murray Rothbard in his Anatomy of the State: “‘We’ are not the government; the government is not ‘us.’”

In opposition to the collectivism of the State, Borges praised and exalted ordinary people, fallible and imperfect, practising their craft one way or the other, in a complex network of individuality and togetherness. Some might call this Human Action. In his poem The Just, Borges enumerates a series of people carrying out daily activities only to conclude that they are, unbeknownst to them, “saving the world.”

In The Other, Borges finds himself talking to his younger double who is writing a new book of poems about “the brotherhood of all mankind”. The dialogue includes this passage:

I thought about this for a while, and then asked if he really felt that he was brother to every living person—every undertaker, for example? every letter carrier? every undersea diver, everybody that lives on the even-numbered side of the street, all the people with laryngitis? (The list could go on.)

He said his book would address the great oppressed and outcast masses. “Your oppressed and outcast masses,” I replied, “are nothing but an abstraction. Only individuals exist.”

As Professor Alejandra Salinas explains, “the political philosophy latent in Borges’s works rests on the belief in a self-sufficient individual, the pre-eminence of liberty, a distrust of government, and nostalgia for anarchy understood as a self-organized order.” [Liberty, Individuality, and Democracy in Jorge Luis Borges]

The Congress is a tale about a failed Uruguayan congressman, Alejandro Glencoe, who decides to create a new representative body of much greater scope, one that could represent people from all over the world. As the debates in the new Congress unfold, they soon run into the impossibility of representing an infinite diversity. At some point, someone suggests that “don Alejandro Glencoe might represent not only cattlemen but also Uruguayans, and also human great forerunners and also men with red beards, and also those who are seated in armchairs.”

The Congress of the World not only fails to represent anyone, but it also becomes a dysfunctional, corrupted, self-serving, ever-expanding, redundant indulgence of don Alejandro, before he decides, faced with the reality of its inadequacy, to dissolve it.

It’s impossible not to draw parallels here with the proposed “Voice” to parliament. As Warren Mundine argues, “[The Voice] is based on a false premise that Indigenous Australians are one homogenous group and will constitutionally enshrine us as a single race of people, ignoring our unique first nations.” It doesn’t take an Argentine genius to understand his point.

Jorge Luis Borges vehemently rejected all forms of collectivism and masterfully wove individualism and liberty into his literary world. Libertarians and classical liberals will gain much pleasure from reading him. The great man from Buenos Aires deserves a place in the Libertarian canon.

I turn again to Our Poor Individualism:

[the utopian] vision of an infinitely tiresome State, once established on earth, would have the providential virtue of making everyone yearn for, and finally build, its antithesis.